Creative adultery

The second I sit down to revise — not write, revise — everything starts to fall apart. That’s when the shine burns off. The thing I made, the thing I loved for a minute there, starts to look flimsy. Like a house with bad plumbing and a slanted floor. And now I live in it. Great.

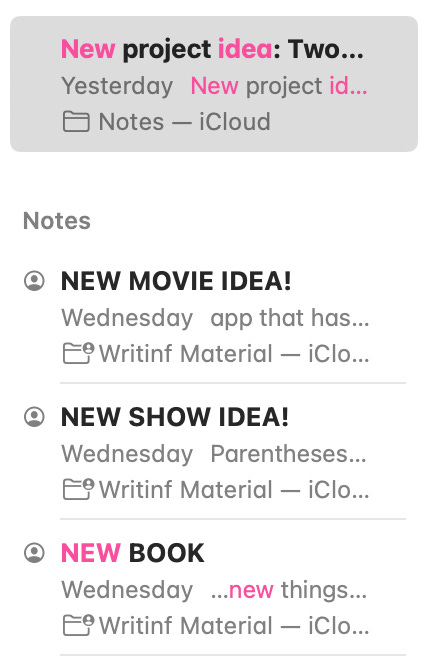

That’s exactly when the new ideas show up.

They barge in uninvited, like exes who still think they have a shot. They don’t care what kind of mess I’m already in. Or maybe they do, and that’s the appeal. “Come away with me,” they say. “This one’s different. I won’t break your heart like that draft did.”

And I want to believe them.

It never happens when I’m in flow, when the sentences come easy and I think maybe, just maybe, I know what I’m doing. No, it always shows up when I’m stuck. When I’m deleting the same word over and over, trying to convince myself a scene matters. When I realize the story I thought was brilliant is actually... fine. Maybe worse.

That’s when the new idea whispers in my ear.

It looks better. Smoother. It doesn’t have pacing issues or dialogue problems. It hasn’t failed me yet. The new idea will write itself.

It won’t. I know that. But it feels true in the moment.

Once, while editing a poem that had turned into a kind of shapeless, unkillable mess, I suddenly had a vision for a novel. A real one. Characters, plot, tension — it was all just there. I stared at the poem and felt something close to hatred. Why was I still here, scraping at something broken, when something better had arrived?

Another time, while trying to rewrite the ending of a chapter that refused to land, I became convinced — for reasons I can’t explain — that I should be writing a screenplay. I opened a blank document, typed “FADE IN,” and sat there like someone waiting for talent to arrive.

This keeps happening. Creative monogamy — staying loyal to one draft, one mess, one half-built world — feels impossible when something new is always appearing at the edge of your vision.

And it is a little like being unfaithful. Not just to the project, but to yourself.

When you start something, you make a quiet promise: I’ll see you through. I’ll finish what we started. Every time you walk away from that — every time you decide this one’s just too messy, too slow, too far gone — you weaken the part of yourself that knows how to finish things. You train yourself to chase beginnings and abandon middles. You start to believe that real work shouldn’t be hard.

And that’s the dangerous part — because sometimes the new idea really is good. Sometimes it has potential. But even the best ones eventually get heavy. They push back. They stop cooperating.

The fantasy fades, and you’re left holding something just as flawed as the thing you left behind. And you realize: it wasn’t the project that was the problem.

It was you.

You’re the one who wants the feeling without the work.

You’re the one who mistakes frustration for failure.

You’re the one who cheats.

I’d love to say I’ve learned. That I’ve figured out how to sit with the doubt and the boredom and the slow parts without reaching for something new. But just last week, while revising this piece, I had an idea for a novel that I was sure, so sure, would change my life, would write itself. I almost stopped writing this to chase it.

Almost.

Instead, I wrote it down on a scrap of paper. I told it I’d come back later, maybe.

And then I turned back to the harder thing. The one I’d already promised. The one that still might be worth finishing.